Part 2 - Lessons Learned from Post Montgomery Cases

The case of Montgomery v. Lanarkshire Health Board 1 in 2015 has had a significant impact on the approach towards consent. However, the law does not stand still, and subsequent cases continue to shape how clinicians should manage the consenting process. Below we look at a few post-Montgomery cases to see how this duty has been applied by the courts.

The original case

Montgomery v. Lanarkshire Health Board (2015) - Supreme Court

Question: Was a doctor negligent in not informing a pregnant diabetic woman that there was a 9-10% risk of shoulder dystocia during vaginal delivery? Answer: YES

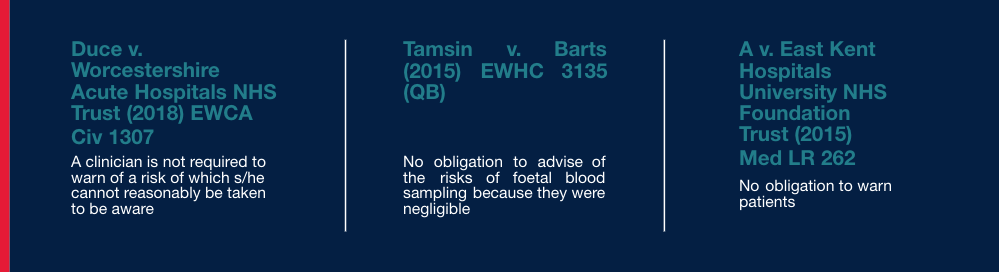

It should be noted that some important exceptions to the Montgomery Duty have emerged. These can be seen in three cases:

Duce v. Worcestershire Acute Hospitals NHS Trust2

It was held that a clinician is not required to warn about a risk that he/she cannot reasonably be taken to be aware.

In this 2008 case it was found that the lack of understanding amongst gynaecologists of chronic pain following abdominal hysterectomy surgery did not justify imposing a duty to warn of that specific risk.

Tamsin v. Barts3

Here it was accepted that there was no obligation to advise of negligible risks. In this case it was specifically risks associated with foetal blood sampling during labour.

A v. East Kent Hospitals University NHS FT4

In this case, a mother brought a claim alleging a failure by the NHS Trust to detect a chromosomal abnormality in her baby during pregnancy. All the tests performed had essentially excluded the abnormality and the Court found that, in those circumstances, there was no obligation to warn about what was a theoretical risk of one of those abnormalities.

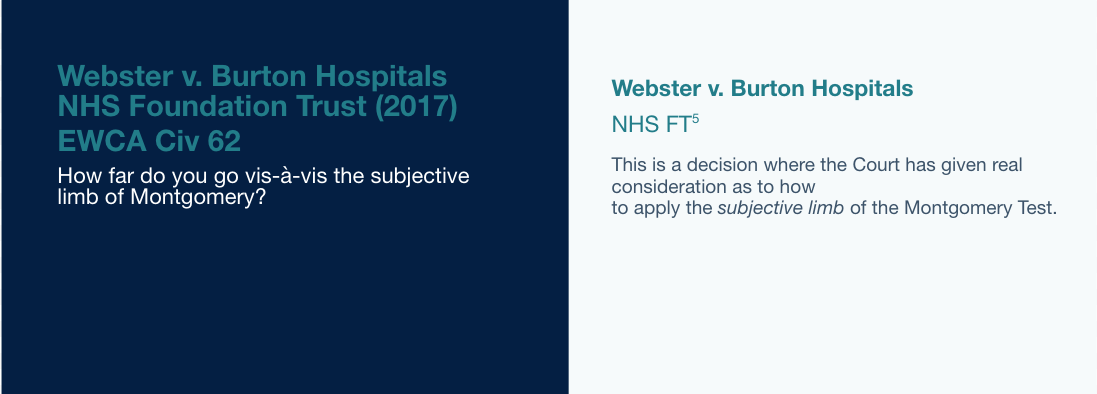

In Part 1 of this Informed Consent Insight Series – ‘Your Duty Explained’ – we examined the subjective limb of the Montgomery Test and how the duty to explain the risks that the particular patient would attach significance to is likely to pose difficulties for clinicians. The following is a good example:

This was a hypoxic birth injury case, where it was established that further ultrasound scanning should have been arranged more frequently due to the baby being small for its gestational age.

The Court found the consultant would or should have informed the mother that the likely combination of features on any further scans were associated with increased risks of delaying the delivery. The Court found that the mother would have attached significance to those risks for three reasons:

- Her evidence was very clear that had there been any suggestion of risk she would have wanted her baby to be delivered sooner.

- She had a university degree in nursing and so perhaps was slightly more knowledgeable about the medical aspects of her situation than the average person.

- She was willing to take responsibility for her pregnancy and had demonstrated that by her decision to leave a hospital stay earlier in the pregnancy against the advice of the doctors.

“The second factor is particularly interesting, as it seems to suggest that doctors are now under a duty to understand the particular and personal concerns of their patients, and that includes in the context of how educated they may be.

From a legal perspective, that would appear to be quite an onerous duty. The obvious question that arises here is: how far do clinicians go with that?” says Stuart Keyden, Partner, DAC Beachcroft.

This is a question we will return to further below.

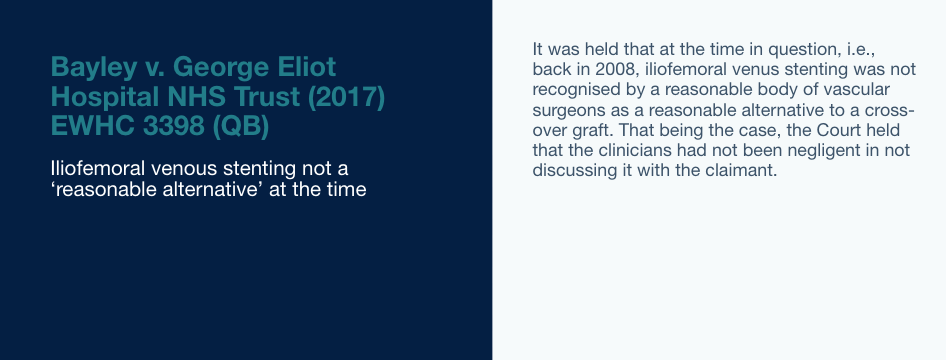

Bayley v. George Eliot Hospital NHS Trust6

This case involved looking at the duty to make the patient aware of reasonable alternative treatments

This case essentially set the scene for the later case of McCulloch, discussed in Part 1 of this Informed Consent Insight Series – ‘Your Duty Explained’ – which confirmed the application of the original Bolam Test to the question of reasonable alternatives.

Thefaut v. Johnson (2017)7

The cases discussed above suggest that some limitations have been placed on the Montgomery duty, but the case of Thefaut v. Johnson would suggest that in some areas, there has been a widening in the scope of the duty.

“This case addressed the issue of what degree of information needs to be given to the patient, not just in the context of risks but also benefits. This is significant because the Montgomery duty arising from the Montgomery case itself discusses material risks and reasonable alternatives but makes no mention of benefits. Arguably, therefore, this case suggests an evolution, or even an expansion, of the Montgomery duty.” Stuart Keyden, Partner, DAC Beachcroft.

The case looked at whether a spinal surgeon was liable for failing to give full and accurate information about the risks but also the prospects of success for a surgery aimed at eradicating pain in the patient’s back and left leg.

In overstating the prospects of success, the Court found that there had been a breach of duty by the surgeon during the consenting process.

“This case suggests that, as well as discussing material risks, the Montgomery duty also extends to giving accurate information as to potential benefits. A duty to give accurate information all round should not perhaps come as a complete surprise as matter of principle, but this is something clinicians will need to bear in mind going forward; they can expect scrutiny across all aspects of the consenting process, and not simply when looking at risks.” Stuart Keyden, Partner, DAC Beachcroft.

A final point of interest in this case is that the claimant (Thefaut) was a midwife. The defence’s suggestion that a reduced consent process was therefore sufficient was rejected. The Court stated that clinicians cannot make assumptions about an individual because that patient is professionally qualified. Putting it another way, clinicians cannot simply water down the consenting process because of the patient’s qualifications.

“The Thefaut case is consistent with the earlier case of Webster, which suggests that the consenting duty now extends to understanding the particular and personal concerns of patients, including in the context of how educated, or medically qualified, they may be. But again, the same question arises: how far do you take that? The reality is that we simply do not currently know unless, and until, the courts grapple with this tricky issue again in the future” says Stuart Keyden, Partner, DAC Beachcroft.

Best advice is to err on the side of caution and ensure rigorous consent processes and practices are implemented - and documented.

For more information contact [email protected]

Sources:

1 The Supreme Court Case Details - Montgomery (Appellant) v Lanarkshire Health Board (Respondent) (Scotland) - www.supremecourt.uk/cases/uksc-2013-0136.html

2 Duce V Worcestershire Acture Hospitals NHS Trust Case Summary - www.casemine.com/judgement/uk/5b2897ee2c94e06b9e19de29

3Tasmin v Barts Health NHS Trust [2015] EWHC 3135 (QB)

Whilst care has been taken in the production of this article and the information contained within it has been obtained from sources that Aon UK Limited believes to be reliable, Aon UK Limited does not warrant, represent or guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, completeness or fitness for any purpose of the article or any part of it and can accept no liability for any loss incurred in any way whatsoever by any person who may rely on it. In any case any recipient shall be entirely responsible for the use to which it puts this article. This article has been compiled using information available to us up to 10/06/2024.