Commitments are nationally determined and at present don’t add up to the 2 Celsius commitment established in Paris. Instead they are closer to 3-3.5 Celsius. They are also subject to political volatility and what is apparent is that there are no guarantees that the policies outlined in 2016 - or more recently - will be implemented.

While predicting individual government commitments to Paris is virtually impossible, what is apparent is that global commitments to climate action are significant and growing. And commitments at the political level are increasingly echoed by central banks, regulators and financial markets, which are placing increasing emphasis on climate action.

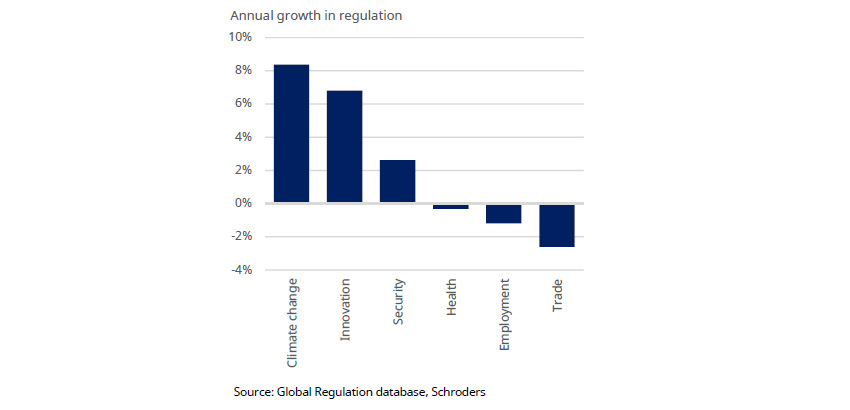

Annual growth in EU regulation by topic since 2000

Commitments have served to increase governmental, regulatory, legal and public pressure to reduce CO2 emissions. Internationally energy firms are facing a combination of measures that are encouraging them to decarbonise at least segments of their portfolio.

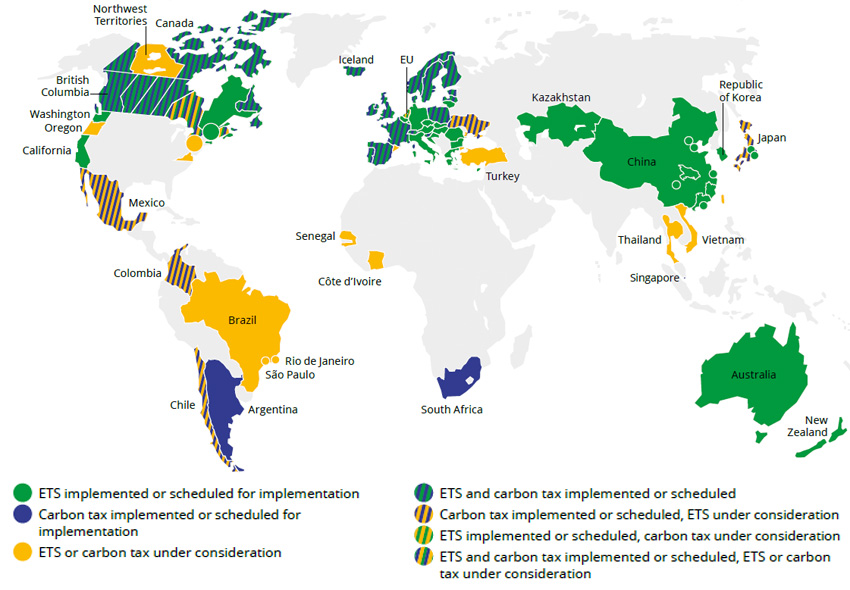

Carbon pricing is one area that is already gaining ground and is likely to become increasingly significant in the years ahead.

BOX OUT

Carbon pricing explained…by the World Bank

Instead of dictating who should reduce emissions where and how, a carbon price gives an economic signal and polluters decide for themselves whether to discontinue their polluting activity, reduce emissions, or continue polluting and pay for it. In this way, the overall environmental goal is achieved in the most flexible and least-cost way to society. The carbon price also stimulates clean technology and market innovation, fuelling new, low-carbon drivers of economic growth.

There are two main types of carbon pricing: emissions trading systems (ETS) and carbon taxes.

ETS – sometimes referred to as a cap-and-trade system – caps the total level of greenhouse gas emissions and allows those industries with low emissions to sell their extra allowances to larger emitters. By creating supply and demand for emissions allowances, an ETS establishes a market price for greenhouse gas emissions. The cap helps ensure that the required emission reductions will take place to keep the emitters (in aggregate) within their pre-allocated carbon budget.

A carbon tax directly sets a price on carbon by defining a tax rate on greenhouse gas emissions or – more commonly – on the carbon content of fossil fuels. It is different from an ETS in that the emission reduction outcome of a carbon tax is not pre-defined but the carbon price is.

The choice of the instrument will depend on national and economic circumstances. There are also more indirect ways of more accurately pricing carbon, such as through fuel taxes, the removal of fossil fuel subsidies, and regulations that may incorporate a “social cost of carbon.”

Source: The World Bank

Globally, carbon pricing is currently set at around USD 2 a tonne – which is unlikely to have any material impact on energy firms - but is already at USD 30 a tonne in Europe. In order for governments to meet the ambitious targets set by the Paris Agreement however, carbon taxes will need to increase to USD 240 a tonne.

While such a number is some way off – and may never be reached in the coming two decades – it provides some indication of the potential pressures energy firms (and other industries with significant carbon footprints) could face if the climate debate hardens and the application of carbon tax gains greater traction.

The rise of carbon tax: an emission trading system (ETS)

BOX OUT

While carbon pricing is gaining ground and global acceptance, there is still no international agreement on the price of carbon, with the topic set to be on the agenda for COP26 in Glasgow in 2021.

Carbon pricing on 5, 10 and 20 year path