And it is apparent that the move to change the energy mix and the pursuit of margin growth in an ultra-low oil price environment, will create new and complex cyber exposures for firms grappling with the need to update, evolve and create efficiencies throughout their operations.

Downstream, refiners and distributors are turning to smart analytics to match supply and demand and increase margins. But by introducing technology that enables real-time monitoring and distribution, firms are connecting the downstream network to the internet and - by extension - cyber risk.

The issue is further complicated by downstream networks that are often old and in hard-to-reach locations – such as dug under cities. This complexity - and the capital outlay needed for new smart systems - will inevitably mean that digital transformation will be pursued in a phased approach.

BOX OUT

Securing engineering systems has become the single most significant challenge facing Chief Information Officers across the energy sector.

Upstream, the engineering challenges are comparable, as firms consider how to build better and more efficient drilling and exploration operations that maximise output and profitability. Again, IT systems are helping to transform operations and bolt-on to existing engineering systems; all through internet-based systems.

By connecting to the internet and utilising technology systems that are coming online at different speeds and stages, firms are however opening themselves up to significant vulnerabilities. As a result, securing engineering systems has become the single most significant challenge facing Chief Information Officers across the energy sector. Firms will need to carefully balance their pursuit of digital transformation with an exponential increase in cyber exposure.

Operational technology environments

Attack vector – phishing

Typical vulnerabilities – employees facing social engineering scams

Impact - theft of operational details or controls, or insertion of malware

Attack vector – malware

Typical vulnerability - external hardware or removable devices, internet or intranet connection

Impact – infection of operational technology resulting in outages, slowdowns and the compromise of system controls

Attack vector - denial of service and botnet attacks

Typical vulnerabilities – operational technology with internet connectivity, or cloud services

Impact – outages of operational technology, servers and databases

Attack vector – advanced persistent treatments

Typical vulnerabilities – coordinated attacks to exploit operational system vulnerabilities and backdoors

Impact – ability to introduce malware and gain control of operational systems

Attack vector – human error or action

Typical vulnerabilities – accidental or deliberate deployment of malware or code injection

Impact - infection of operational technology by malware resulting in slowdown or system failure

Attacks on engineering systems tend to come from two distinct groups: malicious insiders and state-level actors. Insiders typically have greater insight into, and direct access to, engineering vulnerabilities and intellectual property, representing perhaps the most vulnerable link in any firm’s cyber defences. They typically operate inside any cyber defences, while the contractual nature of elements of the energy business means they may not have loyalties apparent in other industries.

At a state-level, cyber attacks tend to target interruption of supply – such as Russian attacks on Ukrainian energy infrastructure during the Crimean conflict (2014-present) – or the theft of intellectual property, including exploration intelligence and technology. This may involve insider activity; or remote attacks, as systems become increasingly connected to the internet.

Exposure to state-level hacking is likely to be further exacerbated by firms hunt for new sources of energy – including alternatives such as LNG and hydrogen. And with a close link between energy firms and the state in many countries, the likelihood of cyber espionage is increased.

Firms also face exposures at the corporate-level – including office systems, websites and financial data – particularly from hacktivists groups targeting energy firms on environmental grounds. Those involved in carbon-heavy areas of the sector are particularly at risk. These attacks tend to be more numerous, but less damaging, with the focus tending to be on corporate IT; as opposed to attacks on operational engineering.

Finally, criminals are targeting client financial information, at both the retail and wholesale level. With customers expecting an increasingly seamless retail experience, energy firms are having to relax the controls that guard the front door of their business – making purchasing simpler and faster, but increasing their exposure to cyber attack.

Risk transfer

The just-in-time nature of engineering system replacement and the age and complexity of existing infrastructure is making for challenging risk transfer conversations , particularly around system resilience and continuity. Upstream, the major concern remains the potential for property damage from a cyber attack. Downstream, it is the potential for business interruption and resultant loss of income. As downstream may also include “direct to consumer” services, this can create an enhanced privacy risk and additional liability that is unlikely to be covered by traditional lines of insurance. What is apparent is that the insurance market is more comfortable dealing with property losses from a cyber event, although coverage continues to evolve and we are seeing growing interest in areas such as environmental liability.

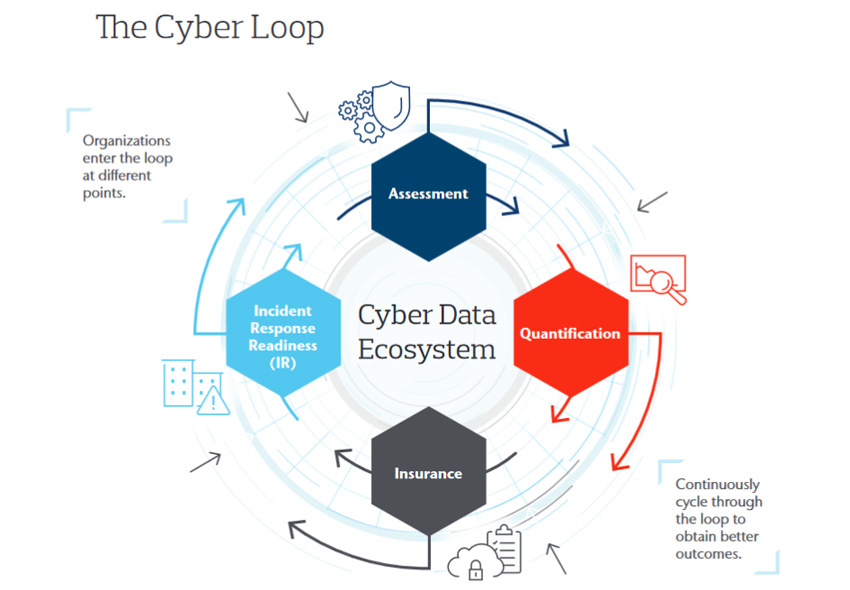

Building resilience: the Cyber Loop

Cyber Loop

Cyber pathways

5 years

Firms will need to extend cyber risk management – which has typically been a strength at the corporate level - into the engineering space as operational and IT systems converge. This will involve protective monitoring and security, with thousands of data points to assess and mitigate exposure. This will require a corresponding investment in smart analytics to ensure appropriate oversight and response to an otherwise overwhelming level of operational data.

5-10 years

Energy firms will find it increasingly challenging to secure cyber coverage as insurers respond to increasing environmental social governance (ESG) pressures. This will be particularly true of European insurers and for the more carbon-intensive areas of the sector.

Markets and clients will have to come to an understanding regarding the efficacy of stand-alone cyber products in industries, like energy, where business is predicated on technology controlling and manipulating the physical environment.

As disparate products combine, and more losses lead to greater understanding of risk factors and costs, more capacity should become available and a clearer approach to transferring cyber risk should emerge.

10-years

An increasingly automated supply chain will drive efficiencies but will inevitably expose operational engineering to cyber attack. In response, firms will need to invest in real-time threat and incident management, with an increasing emphasis on intelligence-led cyber response - both online and across engineering systems.

10-20 years

The carbon transition will have a significant impact on the risk transfer options available for the sector – and if ESG concerns at insurers intensify, it may bring about a crossroads in coverage availability.

Those firms that have a demonstrable handle on their evolving operational exposures - and with the appropriate green credentials – will continue to access coverage; but it is likely that availability, limits and scope of coverage will prove challenging for firms with less insight into their operational exposures and at the more carbon-intensive end of the industry spectrum.

Geopolitical risk – facts on the ground

Our experts

Scott Bolton

Sarah Taylor

Mairtin O’Griofa

Energy firms face a complex array of geopolitical risks as they navigate emerging markets, environmental activism and state-level interventions - and this complexity is only likely to deepen in the coming decades.

People exposures are broad-ranging and firms will need to keep a close eye on evolving risks. Terrorist groups – particularly those with a national, as opposed to international agenda – have targeted oil and gas firms as an outlet for economic, environmental and social grievances.

Groups such as the Niger Delta Avengers, which carried extensive attacks on oil facilities in Nigeria in 2016; or the National Liberation Army (ELN) in Colombia, which has systematically targeted state energy infrastructure; view attacks on infrastructure as a means to force political and economic concessions, from both the state and energy firms.

International terrorist organisations such as Al-Qaeda and Islamic State have also targeted international energy, with incidents such as the In Amenas attack in Algeria in 2013 providing some indication of the seriousness of potential incidents. And while we have seen the collapse of Islamic State and the blunting of Al-Qaeda’s capabilities, the threat posed by Islamist terrorism is likely to remain significant for years to come.

BOX-OUT

Energy firms: in the crosshairs

Over the past five years there have been 375 recorded attacks against energy operations and infrastructure.

Group

Number of attacks

Far Left

173

Far Right

2

Global Islamist

63

National Islamist

8

Nationalist/ Separatist

22

Single Interest

25

Unknown/Not recorded

82

Source: The Risk Advisory Group

Of these 375 attacks, most are concentrated in Colombia, Nigeria, Libya, Syria-Iraq, Afghanistan- Pakistan and India. Other notable concentrations are apparent in Mozambique, Egypt and Saudi Arabia.

Upstream and midstream operations in often politically-challenging parts of the world will remain a concern for firms, with remote facilities and on-site personnel particularly hard to secure.

Kidnap and ransom is often aligned with terrorism; with terrorist and criminal groups turning to abductions to fund their activities. Expats are particularly vulnerable, but groups also target local nationals working for energy firms. The economic impact of COVID-19 has further exacerbated the issue, and Aon has seen a sharp rise in kidnap and ransom cases globally.

Broader civil unrest may also impact firms. Even before the COVID-19 crisis, Aon’s Risk Maps pointed to 3 in 5 countries globally facing the potential for strikes, riots and civil commotion - with significant business interruption implications.

COVID-19 is likely to exacerbate the issue and where industries are particularly badly-hit, or where government responses are perceived to have been weak or excessively economically damaging, there is likely to be a public – and potentially violent – backlash.

Socio-economic grievances are likely to dominate the narrative, and firms need only consider unrest in Hong Kong, Paris and Santiago in 2019, to understand the potential extent and longevity of such incidents.

Energy firms are also likely to find themselves the target of environmental activism. Climate events and greater public support for climate action – including demonstrations – will likely mean energy firms will need to consider whether their offices or downstream operations could be a target of environmental activism.

Political violence – at a state or sub-state level - is also an area of concern, particularly in the Middle East where the conflict between Iran and Saudi Arabia looks set to deepen. Attacks on Saudi Aramco’s Abqaiq and Khurais facilities and attacks on shipping in the Straits of Hormuz in 2019 provide some indication of the complex exposures energy firms face.

It is also likely that the use of more novel forms of attack will increase, whether that is the use of proxies (such as the Houthis in Yemen), technology (such as drones) or cyber terrorism (such as the Shamoon attack on Saudi Aramco and RasGas in 2012).

Firms operating in regions with the potential for political violence will need to closely monitor their exposures – and consider potentially new and novel vectors of attack. For many, the threat alone may be sufficient to dissuade them from investment, with countries like Libya – with significant energy reserves – likely to be passed-up for less challenging locations.

The politics of intervention

When it comes to political risk, the challenges are closely linked to energy pricing, protectionism and currency fluctuations; with COVID-19 further complicating the picture. Energy producing nations have found their finances severely impacted by the pandemic, increasing the likelihood for political interventions in the economy, and should a low oil price environment persist long-term, the temptation to do so is likely to increase.

Energy producing states such as Angola and Nigeria have been severely impacted by the pandemic and may be tempted to revisit long-standing arrangements with energy firms, such as power purchase agreements. In some instances countries may be unable to meet their established obligations due to the challenging energy market and might seek to re-engineer agreements or introduce tariffs to shore-up their finances.

Protectionism - which Aon already highlighted as an issue in its 2019 Risk Maps - is also likely in the face of the pandemic and the ongoing China-US trade war. This may see markets closing to imports, as well as trade and currency restrictions. Currency restrictions are particularly likely where there is a high likelihood of sovereign default - such as in Argentina - or where there is a history of currency controls. This can make the repatriation of profits and currency convertibility a challenge for energy firms, and we would encourage firms to consider how political risk coverage can help them navigate some of these challenges.

Some countries have also introduced emergency powers to respond to the crisis, and there may be a temptation to exploit law-making by decree to re-write and reframe long-standing obligations to international energy. In countries where there is a high concentration of power in the executive, the potential for highly personal decision-making may lead to changes that could persist well beyond the pandemic.

Finally, there is the vulnerability of equipment leased for exploration and production, which is particularly vulnerable to expropriation and default in the face of COVID-19 and the low oil price environment. If you add into that mix other complexities – such as a civil war in the case of Libya – it is apparent that upstream operators are facing something of a perfect storm.

BOX OUT

Geopolitical exposures facing the energy sector

Contract default and/ or currency inconvertibility:Angola, Argentina, Ecuador, Ethiopia, Nigeria and Zambia

Expropriation: Argentina and Gabon

Civil unrest and/ or political violence:Algeria, Chile, Egypt, Iraq and Lebanon

VIDEO

Sarah Taylor

5 years

Countries will still be navigating the fall-out from COVID-19. Its economic impact will not be evenly felt and those countries and sectors worst-hit by the pandemic and the predicted global downturn, will see the most significant increase in politically-motivated interventions, civil unrest and acts of terrorism.

Rising protectionism and the vulnerabilities of supply chains will encourage a rethink of globalisation, which in some instances will involve near-shoring. The realities of the energy sector will likely limit its impact on the sector, but countries such as Canada and the US may place greater emphasis on domestic supply.

Environmental activism is likely to become more entrenched and potentially militant. Economic disparities are likely to result in greater unrest targeting large corporations, and energy firms will likely be among those in the crosshairs.

10 years

The China-US trade war is likely to be further entrenched, with potentially significant implications for firms caught up in the conflict. Tariffs imposed by either side may deepen, with a potential knock-on effect for energy firms and producing states.

Personalities will continue to play a significant role in international politics, as will the stability of regimes in key oil producing nations. Underlying economic and political grievances have the potential to challenge the existing order. While the Arab Spring of 2011 largely failed to bring about democratic change, the potential for a re-emergence of democracy movements – and all that this will mean for incumbent regimes - remains. The potential for civil unrest is significant, as is changes to the existing order.

Energy firms that have traditionally been comfortable dealing with country elites, may see those change in the coming decades in the face of social, economic and environmental pressures – and their seat at the table diminished if the green agenda gathers pace.